RE: WHY WE CAN’T GET ALONG: THE PSYCHOLOGICAL ROOTS OF POLITICAL POLARIZATION

BY MATTHEW JORDAN & VIDUSHI SHARMA, PUBLISHED MAY 1, 2018

Why can’t we get along?

Our brains were shaped by natural selection to think about the issues faced by hunter-gatherers 50,000 years ago. We are designed to live in small tribes, keep social contact with around 150 people, and worry about the safety of our close friends and family. But due to major historical changes—most notably the agricultural, industrial, and information revolutions—we now live in a massively interconnected world with a plethora of complex problems. We have to figure out how to govern billion-person countries, untangle the legacies of racial and religious unrest, and contend with global environmental crises. Needless to say, our hunter-gatherer brains are not perfectly equipped for this task.

To compensate, we rely on certain mental shortcuts guide to our thinking and judgements. We seek out information that conforms to our intuitions and preconceptions, and are quick to dismiss ideas that oppose our own. We believe that our own flaws come from corrigible lapses in judgement, while others’ mistakes come from malice. We think we’re more rational, more intelligent, and less biased than everyone else. And our tribal minds make us think of everyone as belonging to competing teams: left vs. right, Democrat vs. Republican, capitalist vs. communist, pro-life vs. pro-choice, racist vs. antiracist.

This “us-vs-them” module can be switched on or off depending on context, but recent research suggests we are increasingly turning it on in the political realm. Many people around the world view their political affiliation as central to their identity. We discriminate more on the basis of party affiliation than ethnicity or religion, and are unwilling to modify political beliefs in the face of counterevidence. It appears we treat politics the same way we treat sports: evidence could never convince you that you shouldn’t support your favorite team. When people declare their political affiliation, they are not discussing a set of ideas they support; they are expressing their allegiance with a particular team.

But partisan affiliation has dangerous consequences. If you show fans of opposing sports teams footage of a game and ask them whether the referee was biased, they’ll say yes. But fans of each team will claim the referees favored the other team. The same holds for politics. When people are shown footage of a rowdy protest, their answers to basic factual questions—such as whether protestors were harassing pedestrians—depends heavily on whether they agreed with the goals of the protest. Just as with sports teams, political spectators are skewed by their partisan affiliation.

How do people decide what team to root for in the first place? Where do our disagreements actually stem from? To answer this question, we must turn to social and moral psychology.

Cultural Cognition and Moral Taste Buds

The first useful psychological framework we will consider is cultural cognition. To illustrate, it’s helpful to reflect on where some of your own beliefs come from. Pick an issue that you care about strongly. For some of us, climate change fits the bill. Now think: how did you form your views on climate change? Was it by reading academic studies? Did you obtain a degree in atmospheric physics, and from a neutral starting point survey the data and determine that human activity has caused dangerous levels of global warming? Likely not. Your views on most topics can be attributed to where you were born, how you were raised, who your friends are, and your psychological predispositions. Rationality and intelligence have surprisingly little to do with it. This is cultural cognition: our beliefs are largely shaped by cultural identities and peer socialization, not facts or rational arguments.

A key prediction of cultural cognition theory is that disagreements are often not about a lack of factual knowledge. Teaching climate change deniers about atmospheric physics will do very little to change their view. Rather, it will simply enable them to use the facts to more convincingly reinforce their culturally-motivated viewpoint. In fact, the more that individuals knows about topics like climate change, gun control, and nuclear safety, the more polarized they become. Often the people with the most extreme views on either side of an issue tend to have the most factual knowledge about that issue.

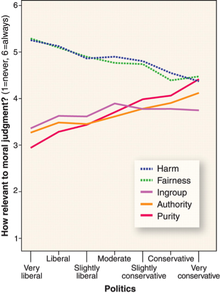

We now turn to our second psychological idea: moral foundations theory. Just as our tongues have taste receptors that are pre-equipped to enjoy certain flavors and find others repulsive, so are our minds equipped with a set of moral taste buds to assess moral information. Instead of detecting sugar or salt, our moral receptors distinguish between six separate moral foundations: harm, fairness, liberty, authority, purity, and loyalty. Our disagreements stem from different sensitivity tunings of these six moral taste buds.

Liberals tend to care a great deal about harm, fairness, and liberty, and very little about authority, purity, and loyalty. Conservatives, by contrast, tend to rate all six factors roughly equally (Figure 1). We can therefore reframe many left vs. right debates in terms of differing moral taste preferences. Liberals are very concerned about economic inequality because it is a violation of fairness, whereas conservatives worry a lot about family breakdown because it points to a violation of loyalty and authority. Liberals worry about the liberty of women to exercise control over their reproductive rights, but conservatives are concerned about harm to unborn fetuses and view abortions as a violation of purity.

The key realization is that your reaction to repugnant ideas is the same as your reaction to repugnant food: automatic, intuitive, and unthinking. When someone doesn’t like a type of food you enjoy, it’s not because they’re stupid, it’s because their taste buds differ from yours. Similarly, when someone disagrees with you politically, it’s often because their differing moral foundations.

The metaphor of moral taste buds is incredible useful, and moral foundation theory allows us to understand the psychological roots of liberal/conservative debates. Crucially, this does not mean that all ideas are equally valuable and legitimate. Ideas must be evaluated on their own merits, not on the moral foundations that may have generated them.

Our brains were shaped by natural selection to think about the issues faced by hunter-gatherers 50,000 years ago. We are designed to live in small tribes, keep social contact with around 150 people, and worry about the safety of our close friends and family. But due to major historical changes—most notably the agricultural, industrial, and information revolutions—we now live in a massively interconnected world with a plethora of complex problems. We have to figure out how to govern billion-person countries, untangle the legacies of racial and religious unrest, and contend with global environmental crises. Needless to say, our hunter-gatherer brains are not perfectly equipped for this task.

To compensate, we rely on certain mental shortcuts guide to our thinking and judgements. We seek out information that conforms to our intuitions and preconceptions, and are quick to dismiss ideas that oppose our own. We believe that our own flaws come from corrigible lapses in judgement, while others’ mistakes come from malice. We think we’re more rational, more intelligent, and less biased than everyone else. And our tribal minds make us think of everyone as belonging to competing teams: left vs. right, Democrat vs. Republican, capitalist vs. communist, pro-life vs. pro-choice, racist vs. antiracist.

This “us-vs-them” module can be switched on or off depending on context, but recent research suggests we are increasingly turning it on in the political realm. Many people around the world view their political affiliation as central to their identity. We discriminate more on the basis of party affiliation than ethnicity or religion, and are unwilling to modify political beliefs in the face of counterevidence. It appears we treat politics the same way we treat sports: evidence could never convince you that you shouldn’t support your favorite team. When people declare their political affiliation, they are not discussing a set of ideas they support; they are expressing their allegiance with a particular team.

But partisan affiliation has dangerous consequences. If you show fans of opposing sports teams footage of a game and ask them whether the referee was biased, they’ll say yes. But fans of each team will claim the referees favored the other team. The same holds for politics. When people are shown footage of a rowdy protest, their answers to basic factual questions—such as whether protestors were harassing pedestrians—depends heavily on whether they agreed with the goals of the protest. Just as with sports teams, political spectators are skewed by their partisan affiliation.

How do people decide what team to root for in the first place? Where do our disagreements actually stem from? To answer this question, we must turn to social and moral psychology.

Cultural Cognition and Moral Taste Buds

The first useful psychological framework we will consider is cultural cognition. To illustrate, it’s helpful to reflect on where some of your own beliefs come from. Pick an issue that you care about strongly. For some of us, climate change fits the bill. Now think: how did you form your views on climate change? Was it by reading academic studies? Did you obtain a degree in atmospheric physics, and from a neutral starting point survey the data and determine that human activity has caused dangerous levels of global warming? Likely not. Your views on most topics can be attributed to where you were born, how you were raised, who your friends are, and your psychological predispositions. Rationality and intelligence have surprisingly little to do with it. This is cultural cognition: our beliefs are largely shaped by cultural identities and peer socialization, not facts or rational arguments.

A key prediction of cultural cognition theory is that disagreements are often not about a lack of factual knowledge. Teaching climate change deniers about atmospheric physics will do very little to change their view. Rather, it will simply enable them to use the facts to more convincingly reinforce their culturally-motivated viewpoint. In fact, the more that individuals knows about topics like climate change, gun control, and nuclear safety, the more polarized they become. Often the people with the most extreme views on either side of an issue tend to have the most factual knowledge about that issue.

We now turn to our second psychological idea: moral foundations theory. Just as our tongues have taste receptors that are pre-equipped to enjoy certain flavors and find others repulsive, so are our minds equipped with a set of moral taste buds to assess moral information. Instead of detecting sugar or salt, our moral receptors distinguish between six separate moral foundations: harm, fairness, liberty, authority, purity, and loyalty. Our disagreements stem from different sensitivity tunings of these six moral taste buds.

Liberals tend to care a great deal about harm, fairness, and liberty, and very little about authority, purity, and loyalty. Conservatives, by contrast, tend to rate all six factors roughly equally (Figure 1). We can therefore reframe many left vs. right debates in terms of differing moral taste preferences. Liberals are very concerned about economic inequality because it is a violation of fairness, whereas conservatives worry a lot about family breakdown because it points to a violation of loyalty and authority. Liberals worry about the liberty of women to exercise control over their reproductive rights, but conservatives are concerned about harm to unborn fetuses and view abortions as a violation of purity.

The key realization is that your reaction to repugnant ideas is the same as your reaction to repugnant food: automatic, intuitive, and unthinking. When someone doesn’t like a type of food you enjoy, it’s not because they’re stupid, it’s because their taste buds differ from yours. Similarly, when someone disagrees with you politically, it’s often because their differing moral foundations.

The metaphor of moral taste buds is incredible useful, and moral foundation theory allows us to understand the psychological roots of liberal/conservative debates. Crucially, this does not mean that all ideas are equally valuable and legitimate. Ideas must be evaluated on their own merits, not on the moral foundations that may have generated them.

It’s also worth noting that the two theories we’ve laid out here—cultural cognition and moral foundations—do not represent “nature versus nurture.” Our inborn dispositions shape our viewpoints as strongly as our cultural identities do. There is no fine line between the two, and we must use all available psychological and sociological theories to make sense of complex human behavior.

We have now seen that our political disagreements often amount to differences in cultural identities and moral sensitivities, not differences in facts. Our minds are not built to impartially weigh evidence; they are built to use evidence to justify our intuitions. The rational part of our brain is like a press secretary, tasked with justifying what our intuitions drive us to do. Fortunately, identifying these mental flaws is the first step to overcoming them.

Overcoming our biases

Now that we understand the psychological roots of political disagreement, what can we do about it? Can we actually overcome our biases, have productive disagreements across ideological lines, and change minds, including our own? We believe the answer is yes, though takes real work.

The first step is to get over the mental reflex that kicks in every time you hear an opposing viewpoint. You know the feeling: you hear something you disagree with and get a pang in your chest, a small flash of revulsion, a wave of self-righteous anger, or a burst of moral outrage. You want to criticize and debate, and can’t believe anyone could be so stupid or evil. This feeling is strong and instinctual, but ultimately unproductive. When we feel disgust or moral outrage, our ability to reason and think critically is impaired. Just as a single unpleasant experience with a type of food might cause you to never eat that food again, exposure to a repulsive idea makes it nearly impossible to engage with it in a meaningful way. And if our goal to understand a wide range of perspectives, change minds, and influence opinions, we must learn to engage with ideas unencumbered by disgust.

The best way to do this is to frame political beliefs using the model of cultural cognition and the moral taste buds. That will reduce the temptation to immediately criticize ideas without understanding them first. Of course, some ideas are legitimately repulsive and some people are genuinely malicious. Fortunately, most of us never interact with them. Rather, the people we talk to are well-meaning individuals whose views were shaped by different internal wirings and life circumstances. Most people are just as reasonable as you are. There is a popular saying: “Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.” We would like to offer a slightly less pithy revision: “Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by moral foundations theory and cultural cognition.”

Taming the moral outrage reflex also requires us to listen to the opinions of people we disagree with. The best way to do this is by finding someone whom you deem intelligent, trustworthy, and respectable, but with whom you disagree over some key issues. (If you cannot find such a person, then you might be the problem.) But you can’t just hear the other side, You you need to understand the other side. You need to familiarize yourself with their lines of reasoning, their ways of thinking, and their moral taste buds. You need to recognize your unquestioned assumptions that others question all the time. This perspective can only help you in the long run. You will gain new insights, add nuance to your own views, and be able to constructively debate your ideological counterparts in a way that makes them feel respected and understood.

It’s important to remember that taming your moral outrage reflex is incredibly challenging, and you can’t take shortcuts. It would be a terrible idea, for instance, to mass-follow extreme voices on Twitter or YouTube. This will just backfire and trigger your disgust reflex even more. The goal is not more exposure, it’s more understanding.

Constructive Disagreement and Mind-Changing

With all of this in mind, how can we actually move forward and change minds, including our own? It is very difficult to change minds with facts, because we rarely use facts to form our views in the first place. Moreover, the whole idea of “changing someone’s mind” is flawed. Ideas aren’t like switches that can be turned on or off in someone’s brain. Rather, the process of mind-changing is gradual. As we learn more about an issue and speak to more people, we incrementally update our views. Few people will ever change their mind on the spot because of brilliant arguments, unless they’re already very sympathetic to what is being argued.

It is useful to think of the mind like a rider on an elephant. Reason and logic are the rider, while emotions and intuitions are the elephant. Though the rider has some control over where the mind will go, the elephant is ultimately in charge. When we present a person with facts and data, we are only speaking to the rider. But when we form strong bonds, establish trust, and show a willingness to engage in productive discussion, we are engaging the elephant, and therefore making a person much more likely to take kindly to our views. So how can we speak to the rider and motivate the elephant?

First, and perhaps most importantly, build well-rounded relationships with people who disagree with you. It becomes hard to sideline conservatives as bigots after spending hours over tea with religious friends, or to scoff at social justice warriors after joining a vegetarian co-op with student activists. Befriending your ideological counterparts and engaging in activities beyond politics will allow you to transcend stereotypes and have more productive political conversations, too. In situations when you’re meeting someone for the first time, start conversations and relationships with questions that build trust—ask about each other’s hometown, mentors, or values.

Once you’ve established some common ground, it will become much easier to exchange views on political issues. In the process of giving and receiving arguments, acknowledge the gaps in your knowledge and be especially open and vocal about areas where your opinions might be subject to change. Discovering ignorance and doubt are steps in the right direction! Instead of focusing on how to best change someone else’s mind, think about how and when to change your own. And even when you cannot fathom changing your mind on a certain issue, focus on learning what you can from your interlocutors. This process will both humanize your political opponents and help you both think independently, instead of blindly following your party’s views on a slew of unrelated issues.

In sum, humans are complicated. We are civilized apes who live in a world with more information than our brains were built to handle. We’re therefore equipped with mental shortcuts to help us make sense of the world, and one of the most pernicious is our tendency to form moral and political tribes. We see our ideological opponents as evil, and don’t have the self-awareness to recognize our own flaws and biases. Fortunately, we can take concrete steps to improve. We can acknowledge that everyone’s worldview is shaped in part by their moral dispositions. We can reflect on our own beliefs, and recognize that they’re not a product of our brilliance, but much more often of circumstance. We can try to understand the logic underlying opinions we disagree with, and always try to learn something from our ideological opponents. We can remember that mind-changing is about establishing trust and incrementally updating views, not using logic to flip a mental switch. And perhaps most importantly, we can accept that not everyone will agree with you, and that’s OK. Progress only happens when ideas butt heads.

We have now seen that our political disagreements often amount to differences in cultural identities and moral sensitivities, not differences in facts. Our minds are not built to impartially weigh evidence; they are built to use evidence to justify our intuitions. The rational part of our brain is like a press secretary, tasked with justifying what our intuitions drive us to do. Fortunately, identifying these mental flaws is the first step to overcoming them.

Overcoming our biases

Now that we understand the psychological roots of political disagreement, what can we do about it? Can we actually overcome our biases, have productive disagreements across ideological lines, and change minds, including our own? We believe the answer is yes, though takes real work.

The first step is to get over the mental reflex that kicks in every time you hear an opposing viewpoint. You know the feeling: you hear something you disagree with and get a pang in your chest, a small flash of revulsion, a wave of self-righteous anger, or a burst of moral outrage. You want to criticize and debate, and can’t believe anyone could be so stupid or evil. This feeling is strong and instinctual, but ultimately unproductive. When we feel disgust or moral outrage, our ability to reason and think critically is impaired. Just as a single unpleasant experience with a type of food might cause you to never eat that food again, exposure to a repulsive idea makes it nearly impossible to engage with it in a meaningful way. And if our goal to understand a wide range of perspectives, change minds, and influence opinions, we must learn to engage with ideas unencumbered by disgust.

The best way to do this is to frame political beliefs using the model of cultural cognition and the moral taste buds. That will reduce the temptation to immediately criticize ideas without understanding them first. Of course, some ideas are legitimately repulsive and some people are genuinely malicious. Fortunately, most of us never interact with them. Rather, the people we talk to are well-meaning individuals whose views were shaped by different internal wirings and life circumstances. Most people are just as reasonable as you are. There is a popular saying: “Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.” We would like to offer a slightly less pithy revision: “Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by moral foundations theory and cultural cognition.”

Taming the moral outrage reflex also requires us to listen to the opinions of people we disagree with. The best way to do this is by finding someone whom you deem intelligent, trustworthy, and respectable, but with whom you disagree over some key issues. (If you cannot find such a person, then you might be the problem.) But you can’t just hear the other side, You you need to understand the other side. You need to familiarize yourself with their lines of reasoning, their ways of thinking, and their moral taste buds. You need to recognize your unquestioned assumptions that others question all the time. This perspective can only help you in the long run. You will gain new insights, add nuance to your own views, and be able to constructively debate your ideological counterparts in a way that makes them feel respected and understood.

It’s important to remember that taming your moral outrage reflex is incredibly challenging, and you can’t take shortcuts. It would be a terrible idea, for instance, to mass-follow extreme voices on Twitter or YouTube. This will just backfire and trigger your disgust reflex even more. The goal is not more exposure, it’s more understanding.

Constructive Disagreement and Mind-Changing

With all of this in mind, how can we actually move forward and change minds, including our own? It is very difficult to change minds with facts, because we rarely use facts to form our views in the first place. Moreover, the whole idea of “changing someone’s mind” is flawed. Ideas aren’t like switches that can be turned on or off in someone’s brain. Rather, the process of mind-changing is gradual. As we learn more about an issue and speak to more people, we incrementally update our views. Few people will ever change their mind on the spot because of brilliant arguments, unless they’re already very sympathetic to what is being argued.

It is useful to think of the mind like a rider on an elephant. Reason and logic are the rider, while emotions and intuitions are the elephant. Though the rider has some control over where the mind will go, the elephant is ultimately in charge. When we present a person with facts and data, we are only speaking to the rider. But when we form strong bonds, establish trust, and show a willingness to engage in productive discussion, we are engaging the elephant, and therefore making a person much more likely to take kindly to our views. So how can we speak to the rider and motivate the elephant?

First, and perhaps most importantly, build well-rounded relationships with people who disagree with you. It becomes hard to sideline conservatives as bigots after spending hours over tea with religious friends, or to scoff at social justice warriors after joining a vegetarian co-op with student activists. Befriending your ideological counterparts and engaging in activities beyond politics will allow you to transcend stereotypes and have more productive political conversations, too. In situations when you’re meeting someone for the first time, start conversations and relationships with questions that build trust—ask about each other’s hometown, mentors, or values.

Once you’ve established some common ground, it will become much easier to exchange views on political issues. In the process of giving and receiving arguments, acknowledge the gaps in your knowledge and be especially open and vocal about areas where your opinions might be subject to change. Discovering ignorance and doubt are steps in the right direction! Instead of focusing on how to best change someone else’s mind, think about how and when to change your own. And even when you cannot fathom changing your mind on a certain issue, focus on learning what you can from your interlocutors. This process will both humanize your political opponents and help you both think independently, instead of blindly following your party’s views on a slew of unrelated issues.

In sum, humans are complicated. We are civilized apes who live in a world with more information than our brains were built to handle. We’re therefore equipped with mental shortcuts to help us make sense of the world, and one of the most pernicious is our tendency to form moral and political tribes. We see our ideological opponents as evil, and don’t have the self-awareness to recognize our own flaws and biases. Fortunately, we can take concrete steps to improve. We can acknowledge that everyone’s worldview is shaped in part by their moral dispositions. We can reflect on our own beliefs, and recognize that they’re not a product of our brilliance, but much more often of circumstance. We can try to understand the logic underlying opinions we disagree with, and always try to learn something from our ideological opponents. We can remember that mind-changing is about establishing trust and incrementally updating views, not using logic to flip a mental switch. And perhaps most importantly, we can accept that not everyone will agree with you, and that’s OK. Progress only happens when ideas butt heads.

![::[REDIRECT]::](/uploads/1/1/7/5/117580717/redirect.jpg)